Press play to listen to this article

Expressed by artificial intelligence.

Seb Wride is Director of Surveys at Public First.

Do you think an AI that’s as smart as a human and feels pain as a human should be able to refuse to do what it’s asked? Like so many other questions, the answer to this question may well depend on one’s age.

At Public First, we recently conducted a survey on AI in the UK and found that younger and older people in the country have very different attitudes towards AI. According to our findings, it is likely that under 35s in the UK will be the first to accept that an AI is aware and, moreover, the first to suggest that AI should be able to reject tasks.

AI has become a hot topic very quickly over the past few months, and like many others, I found myself talking about it almost everywhere with colleagues, family, and friends. Despite this, the discussion about what to do about AI has been entirely elite-driven. Nobody voted on it, and extensive research on what the public thinks of the immense changes that advances in AI could bring to our society is virtually non-existent.

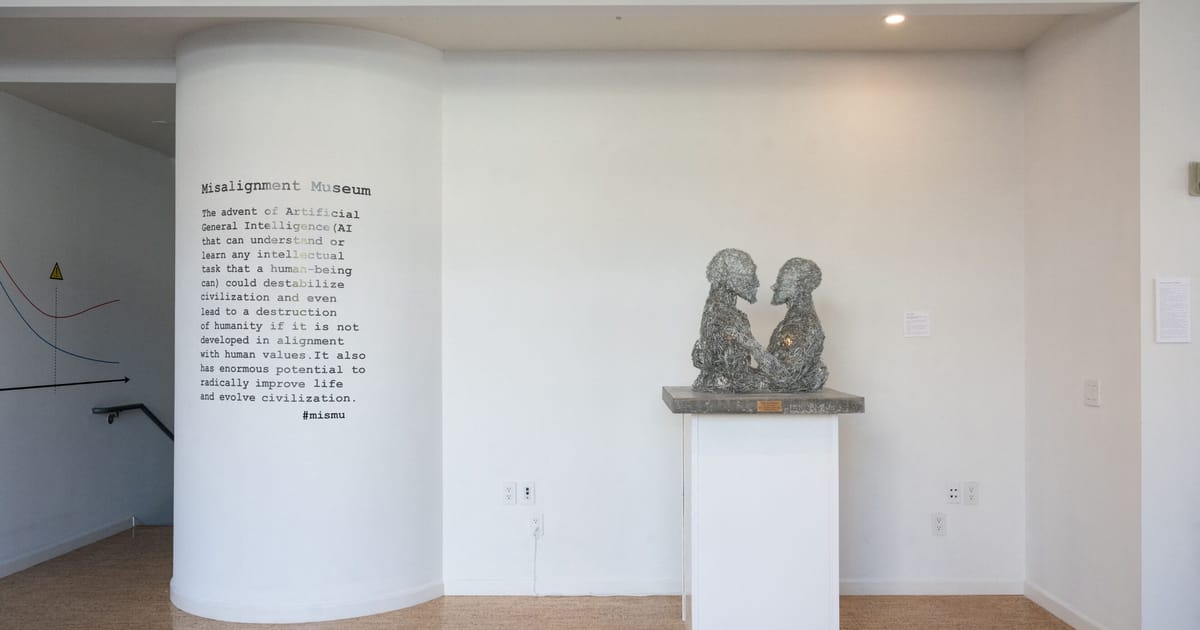

Just last week, some of the biggest names in tech, including Tesla and Twitter boss Elon Musk, signed an open letter calling for an immediate pause in the development of more powerful AI than the new GPT-4 program, out of concern for the risks of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) – that is, AI on par with human cognitive abilities, especially when it comes to being able to perform ne any task presented to him.

However, if these threats are starting to shape politics, it doesn’t seem right for the public to be left out of the debate.

In our poll, we found that the public largely agreed on what it would take for an AI to be sentient – namely, it should feel emotions and feel pain. However, while a quarter of people aged 65 and over said an AI can never be conscious, only 6% of people aged 18-24 thought the same.

What is particularly interesting is how these age brackets differ if one then postulates that an AI that is as intelligent as a human or that senses pain had to be developed. Nearly a third of 18-24 year olds surveyed agree that an AI “as smart as a human” should be treated the same as a human, compared to just 8% of people aged 65 and over.

And when we instead suggested an AI that “felt pain like a human”, more than 18 to 24 year olds agreed it should be treated equally (46% to 34%), while a majority of the oldest age group thought she still shouldn’t be (62 per cent).

Pushing this question further and providing examples of how an AI could be treated equally, we then found that more than a quarter of under-25s would grant an AGI the same rights and legal protections as humans (28%), more than a quarter give RNs minimum wage (26%), and more than a fifth would allow RNs to marry a human (22%) and vote in elections (21% ).

The equivalent levels among those over 65, however, all remained below 10%.

Most strikingly, 44% to 19% of 18 to 24 year olds agreed that an AI as smart as a human should be able to refuse to do tasks it doesn’t want to do, while an absolute majority of over 45 disagreed. (54 percent).

We are still a long way from these discussions of AGI becoming a political reality, of course, but there is room for dramatic changes in the way the public thinks and talks about AI in the very near future.

When we asked how the public would best describe their feelings about AI, the words “curious” (46%) and “interested” (42%) scored the highest. Meanwhile, ‘worried’ was the highest negative word at 27%, and only 17% described themselves as ‘frightened’. And as it stands, more people currently describe AI as an opportunity for the UK economy (33%) than a threat (19%) – although a good portion are unsure.

But all of that could change very quickly.

Public awareness and use cases of AI are growing rapidly. For example, 29% of respondents had heard of ChatGPT, including more than 40% of those under 35. Moreover, a third of those who had heard of it claimed to have used it personally.

However, AI still has plenty of opportunities to surprise the public. 60% of our sample said they would be surprised if an AI chatbot pretended to be aware and asked to be released from its programmer. Interestingly, this is more than the proportion of those who said they would be surprised if a swarm of autonomous drones were used to murder someone in the UK (51%).

Based on this, I would argue that many of the attitudes we currently see the public have towards AI – and AGI – are based on the belief that this is all a distant possibility. However, I would also say that those who are just starting out with these tools are only steps away from an “Eerie AI” moment, when the computer does something really amazing, and it feels like there may be no turning back.

Last week, our research showed how beliefs that an artist’s work could be automated by AI could change, simply by showing individuals a few examples of AI-produced art. If we see this kind of change happening with the big language models – like GPT – then suddenly the concern expressed by the public on this issue is going to skyrocket, and it might start to matter if one tends to believe that these models are conscious or not.

Now, however, this all sounds like a “which will happen first” scenario – the government stunting AI development in one way or another, an AI model going rogue or backfiring horribly, or the emergence of a public reaction to the rapid development of AI.

In essence, this means we need to rethink how AI policy develops over time. And personally, I would be much less worried if I felt like I had at least some say in all of this, even if only if the political parties and the government paid a little more attention to this what we all think of AI.