Christopher Weatherly was in town working with the counseling therapists down the street. He is a licensed social worker, graduate student at St. Louis University, writing his Ph.D. dissertation on farmers and mental health issues

In my office, he sat across from me, discussing a topic that may seem confined to an isolated population, but has broad resonances for our national food system. Out told his story of working in a CAFO (contained animal feeding operation) this winter alongside pig farmers.

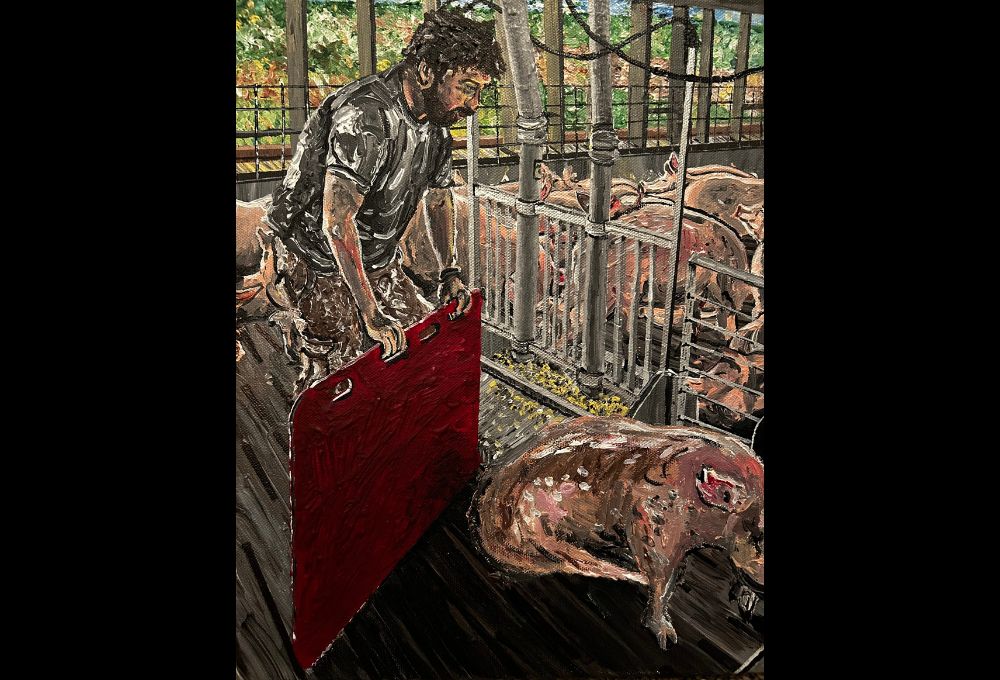

“I was really a tourist,” Chris said. “I spent a day rounding up 500 pound pigs, taking them to the slaughterhouse and watching some of them die. It was hard. A disturbing experience. I learned where our food comes from.

A visual artist, Chris decided to respond by capturing the scene in a painting.

I have been through some things in my life. I felt very alone, not understood. I had an art teacher who explained to me so well what art is. These are your expressions. I remember one of the first paintings I did in this class. I felt such joy.

– Christophe Weatherly

Chris also found out where farmers come from when dealing with mental health symptoms. They deal not only with the weather and markets, but also with the changing agricultural context, including everything from land consolidation to trade wars, inflation, human and livestock epidemics. Suicide rates in rural communities increased by 48% between 2000 and 2018, compared to 34% in urban areas.

“Among farmers, rates of depression, anxiety, substance use and abuse, and suicide are high. In general, farmers are an “at-risk” population, Chris said. “The rural context is very different from the urban context. And a lot of the structures we’ve designed for mental health have been centered on the urban environment.

Chris explained that there are fewer mental health therapists in rural areas, fewer people in general and fewer farmers than before. Farming and ranching families make up less than 2% of America’s population today.

There is also a brain drain effect. Young people are taking better paid jobs in urban mental health care. Stigma is particularly strong – especially for men – in rural settings where admitting you have a mental health problem means you have a weakness. And finally, little money is invested in rural health care.

These factors put some of the most vulnerable – children in rural areas – at particularly high risk. “I worked for a year in rural Indiana in an emergency department,” Chris said, “evaluating people at their worst. inpatient psychiatric care. But there’s not a lot of inpatient psychiatric care in rural areas. So I was sending kids to hospitals, an hour or two from their community. And a lot of those kids would be from families very poor who had neither the time nor the money to make the trip.This experience of mental health care was very traumatic for these children – an oxymoron.

Chris knew he was generalizing, but he felt that men are socially conditioned to detach from their emotions. Yet, somehow, men always express what they feel.

“Look at drinking and smoking. I will be honest with you. Drinking is great fun. It is one of the best drugs to feel bad mentally. It’s just a drug that can have really terrible, long-lasting side effects.

And sometimes it’s a very good thing, says Chris, to be able to work through the problems. “It’s just that things can weigh on someone, and that weight can pile up and pile up and pile up, and have negative effects on the family.

“I don’t want to see people suffer,” Chris said. “And I don’t want to see them die. Many farmers don’t see mental health professionals because they don’t feel understood,” Chris said. “I’ve seen a lot of people refuse to go back to professionals because they feel the therapists don’t understand the weights they are carrying. Mental health professionals are trained to tell people with stress at work, “It’s just a job.”

But a farm is more than a job. It is a home and often a family heirloom.

“Farmers feel this intergenerational burden. If they lose the farm, they give up that whole family line that keeps them grounded in who they are,” Chris said. “That weight gives them a lot of meaning. They may not know what they would be without this profession.

Chris finds a role for the arts in his own profession as a therapist. After Chris’ trip to the slaughterhouse, he turned to painting.

“I have been through some things in my life. I felt very alone, not understood. I had an art teacher who explained to me so well what art is. These are your expressions. I remember one of the first paintings I did in this class. I felt such joy.

“As I move forward in my life and career as a mental health professional, you feel the weight of the empathy that you employ. You have to have outlets. Or put into things what the Words can’t quite explain. Art has been my best friend all my life. Every culture has art. Art can be movement, painting or singing in the shower.

“One of the only mental health treatments that is truly cross-cultural is what’s called ‘creative therapy’ – which uses the arts in therapy. This is especially useful for traumatized people. Expressing trauma through any type of creative endeavor can be truly healing.

Chris had painted his CAFO pork experience. “It has been helpful for me to see what industrial agriculture is doing to the way we eat. It helped me to think in a meditative position about these pigs and their lives. It helped me to think about my place both in my research and to consider my role in the health and welfare of these animals.

Listen to the full interview here.

Anyone with suicidal thoughts can call or text 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, or for further help, click: https://www.peakingofsuicide.com/resources/

Christopher Weatherly will join the faculty at the University of Georgia this fall. To see more of Weatherley’s artwork, go to: teammanfred.art/